COVID-19 has presented myriad challenges for state and local governments and public health departments. Many were never equipped to handle real-time reporting to the public prior to April; even those that were had to learn a new lexicon before they could responsibly report on COVID (cases, hospitalizations, ventilators, COVID-Like Illness...). Pair this with a decentralized system of healthcare and government, and it's no wonder the format and level of detail of the data varies from one location to the next.

Nashville's Metro Public Health Department, for its part, launched a "Roadmap for Reopening" in mid-April: A set of "data-driven, not date-driven" metrics which, when met, would assure residents and local leaders that it was safe to move to the next "Phase" of reopening. So far, so good.

But among these metrics are two which deal with hospital capacity: One which tracks the percentage of floor beds available in area hospitals, and another which tracks the percentage of ICU beds. This calculation seems pretty straighforward, right? You just take the number of patients currently in hospitals (the "hospital census"), and divide that by the number of beds, to get a percentage. Metro declared that 25% of beds should be available at any one time, before reducing the thresholds down to 20% sometime in May.

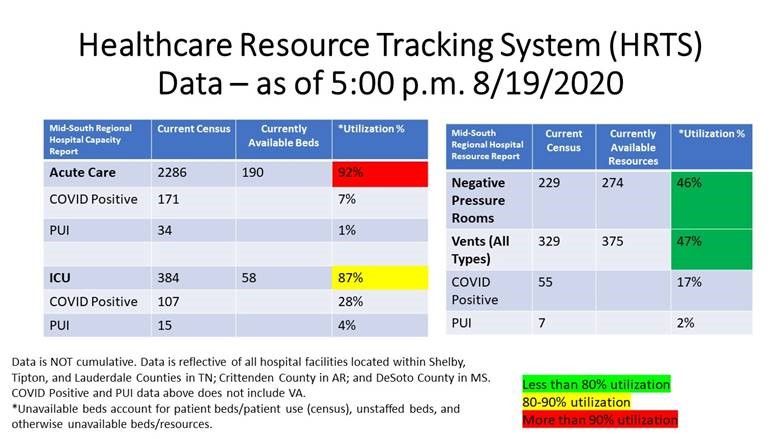

So, about that calculation: You just need a numerator and denominator. Simple, right? Well... no, because Metro doesn't publish those numbers, as other cities do. Memphis, for example, provides an easy-to-read table as part of Mayor Strickland's daily updates there:

From the above, we know that there are 2,286 total patients in Memphis-area hospitals, and 190 available beds. This means that there are 2,476 total beds, and that 92% are taken by patients of all types. We also know that 171 beds are taken by "COVID Positive" patients, or 7% of the total.

What are the relevant figures in Nashville? We don't know, of course, because the city doesn't publish them (we wish they did). But with some investigation, we can make reasonable estimates for what bed and patients counts are now, and have been in the past.

First, let's look at some publicly available data. The Tennessee Department of Health publishes a statewide listing of hospitals and bed counts in each, most recently updated in June 2020 (during the pandemic). Tally up the number of beds in Davidson County, and you get 4,264 beds. We also have this private database of hospital locations, bed counts, and average utilization; filtering down to the 13 hospitals in Nashville yields a similar total of 4,186 beds. Two sources (one public, one private), similar totals; we seem to be on the right track.

But we can further triangulate this capacity figure using another source: statements by local health officials to the press. Jump back to the beginning of the COVID-19 timeline, and you find this Nashville Post article from March 26, which quotes Metro Coronavirus Task Force leader Alex Jahangir as saying that Nashville "has about 3,000 available beds and 1,600 intensive care unit beds, and they are making plans to build emergency facilities if necessary." It's unclear, here, whether the ICU beds are considered in the total bed count; nevertheless, we either have 3,000 beds with room to expand, or 4,600 beds. Jahangir subsequently announced that the city was expanding hospital capacity to keep up with demand during late July, suggesting that this number is flexible and can change over time.

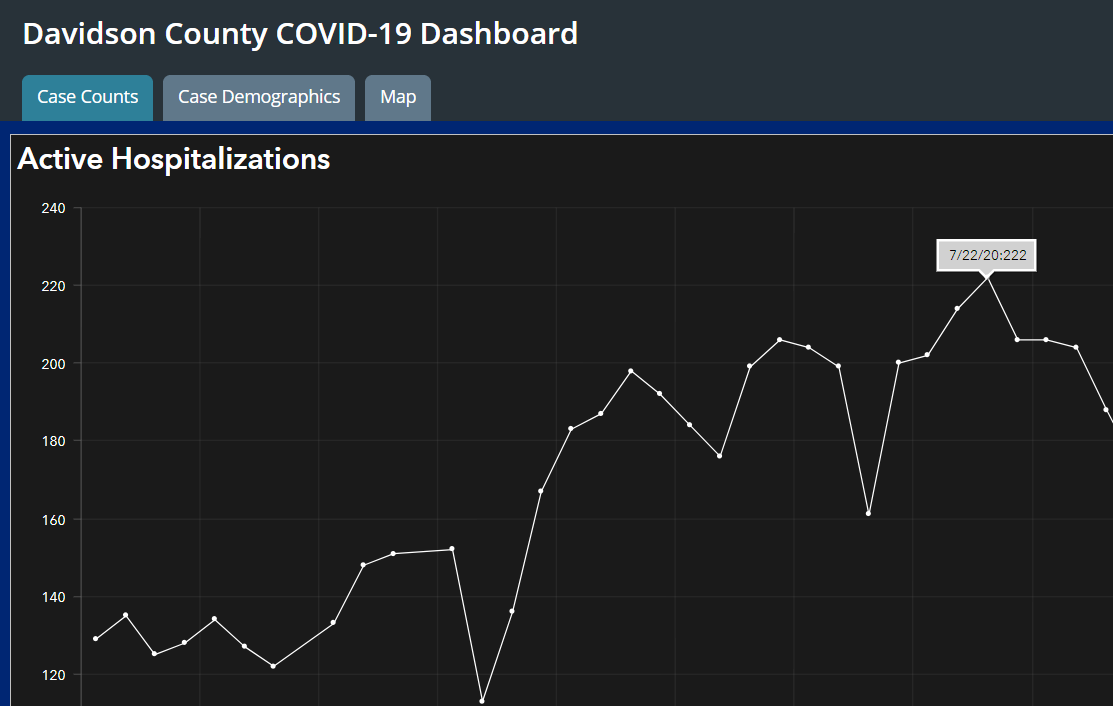

Finally, we DO know the number of COVID patients in hospital, as this information is published on the Davidson County COVID-19 Dashboard. As of August 20, there were 160 COVID-19 patients in hospital, a number that has ranged from about 130 in mid/late June, up to a peak of about 220 in late July. This hardly supports Jahangir's late July claim that "hospitals are getting full of COVID patients," based on what we know about the city's overall capacity; 220 is something between 4.8% and 7.3% of total hospital capacity based on Jahangir's own statements from March (depending on how you want to interpret them).

The above sources and figures were used to create this very website's Nashville Hospital Capacity Tracker - it's our best estimate of how many hospital beds are in Nashville, and of those, how many are available, how many are taken by COVID patients, and how many are taken by non-COVID patients.

Recently, though, statements by Dr. Jahangir have cast doubt over how the city is calculating the capacity metrics used on its website. Here are a couple notable examples:

- In an interview Tuesday evening with WSMV-TV, Jahangir stated that "three weeks ago, 13% of all people hospitalized in Nashville, 222 individuals, were hospitalized because of COVID." This implies a total patient count of roughly 1,708 on the date in question, which was July 22, according to the county's dashboard:

But on that same date, Metro Nashville reported that available bed capacity was just 17%. This means that the 1,708 total patients made up 83% of beds. Do the math, and the implication is that there were 2,057 beds available - far below all of the earlier estimates from data sources, as well as from Jahangir himself in March. Jahangir continues in his August 18 interview: "Today that number is 9% [of total patients are COVID patients], or I believe 150 people, 160 people." This works out, again, to something like 1,700 total hospital patients - a number, you'll note, that is virtually unchanged from the "peak" in late July! - on a date which Metro Nashville reported, again, that available bed capacity was just 17%. These two virtually identical numbers suggest that Metro Nashville has been using a total bed count of 2,000 - 2,100 in their calculation of hospital bed capacity - again, far below the numbers that we can identify from other sources.

- Jahangir repeats these numbers in the Mayor's daily press briefing on August 18 as well (skip to 6:00).

So, what is going on here? Did the number of beds decrease since late March (per Jahangir) and since June (per the TN Department of Health)? If so, does Nashville have the ability to increase its hospital capacity once again in the event of a surge?

Or, perhaps Nashville is counting only staffed beds (that is, beds which can be attended to by nurses and physicians), and not the total number of physical beds, in its calculation of capacity? Memphis' numbers refer to this in a footnote, so perhaps this explains the discrepancy. But once again: Does Nashville have the ability to staff these additional 1,000 - 2,500 beds in the event of a surge?

Or, in the most pessimistic view: Is Nashville manipulating the denominator in their calculation of hospital bed capacity to achieve a desired result? We won't, and don't, accuse them of that without evidence.

We don't know the answers to these questions. It doesn't have to be this way - Nashville draws their data from the same state database - and a calculation involving simple division could very easily be explained to the public and clarified. Memphis provides this context, which is critical to our understanding of whether their hospital system is equipped to handle additional case loads from COVID-19.

Until someone demands answers, though, we're left wondering.